On July 8, 2015, I lost a legal battle against Automattic over thesis.com, despite owning the trademarks for Thesis and Thesis Theme in the website software space.

Many of you have probably read the initial account of what happened on WP Tavern along with all of the comments. Unfortunately, as is customary with legal disputes involving WordPress that receive widespread criticism, Jeffr0 closed the comments on that post, effectively shutting down the conversation.

However, there is a lot to talk about on this issue. I’d like to walk you through how Automattic and I ended up in a legal battle for a domain, why this was connected—in a very personal way—to a public disagreement that happened years ago, and finally, what this could mean for business owners who operate in the WordPress ecosystem.

I think the most important place to start is by asking: Why would Automattic—a website software company with over $300 million in funding—buy thesis.com when I owned the trademark for Thesis in the website software space?

Negotiating a Price for Thesis.com

By late 2012, my premium WordPress Theme, Thesis, had grown to tens of thousands of users, and I realized it might make sense to invest in the domain, thesis.com. Business was going well enough that I could justify the cost, so I decided to give it a shot.

Based on domain records, thesis.com had been owned continuously but never used since 1999. Why is this fact important? It often means there isn’t much competition for a domain, and in cases like this, it’s not unheard of for the domain to go for a fair price.

In February 2013, armed with this knowledge and also SEDO’s domain pricing information, I opened negotiations with a domain broker named Larry of GetYourDomain.com in an attempt to purchase thesis.com. I opened with an offer of $37,500 (which I still think is an awful lot to pay for an unused domain).

Larry thought the domain was worth quite a bit more and countered with $250,000. Well, that escalated quickly!

Consider that cabs.com sold for $50,000 in 2014; given that the taxi industry in the US alone is worth $11bn per year, it is reasonable to think thesis.com would carry a lower price tag.

After reading his counter, I felt like this negotiation was dead on arrival. I didn’t think the market value for thesis.com exceeded $50,000 and couldn’t see how Larry would have any reason to think otherwise.

But I was wrong.

There was some back and forth, and Larry ultimately dropped the price to $150,000, which he still thought was reasonable. I didn’t see myself or anyone else in my position paying that much for a domain, so I decided to back out and accept the fact I probably wasn’t going to end up with thesis.com.

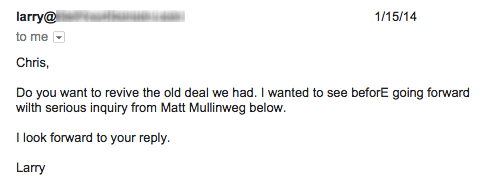

Nine months later, out of the blue, I received an email from Larry:

Figure 1. Email from Larry suggesting Matt Mullenweg’s interest in thesis.com

Well, I wasn’t expecting that. Apparently, WordPress and Automattic founder Matt Mullenweg wanted to buy thesis.com as well.

This was interesting because, back in 2010, Matt and I had been involved in a very public interview and debate on Mixergy over Theme licensing.

During that debate, I got defensive and acted like an asshole. At the time, I was woefully ignorant about software licensing, and I felt as though I was being backed into a corner and asked to accept something I didn’t fully understand. Instead of handling it in a measured, polite manner, I was a jerk.

I made a mistake, and I paid dearly for it.

The interview caused a chain reaction of negative events for Thesis, and we lost a huge portion of our business. It also had a significant influence on the way people perceive me to this day, five years later.

The WordPress community’s reaction towards me was incredibly negative, but on top of that, Matt did whatever he could to further damage what was left of my business. His most blatant effort in this regard was making a public offer to buy Thesis customers the premium, GPL-licensed Theme of their choice if they quit using Thesis.

Few people seemed to mind this tactic. I had become a despised figure within the community, and I got what I deserved.

This was a tough—and especially costly—lesson to learn, but it was over, and I needed to conduct myself better. Rather than linger on the past or hold a grudge, I moved on, turned my attention toward the future of the business, and put this issue behind me.

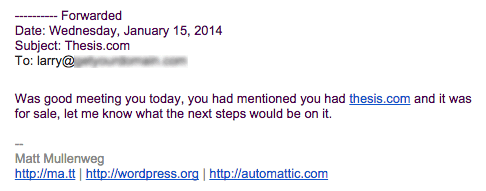

But on January 15, 2014, over three-and-a-half years later, Larry forwarded me Matt’s inquiry into thesis.com:

Figure 2. Email from Matt inquiring about thesis.com

At this point, I still thought Larry was just trying to get some leverage in the negotiations. Why would Matt wait over three years to try and buy thesis.com?

And to spend upwards of six figures on a domain years after any kind of interaction between us? That didn’t make sense to me.

Why would the founder of a high-profile, VC-funded company even think about wasting significant resources on something like this?

Larry had to be bluffing.

Regardless, the fact he brought up Matt gave me the impression he really just wanted to close a deal. I countered with the following:

Larry,

The truth is, I own the trademark for Thesis as it relates to web software and websites. If Matt were to buy it, he would have to change everything he’s done and plans to do; otherwise, the domain would be almost useless to him.

I do admire you trying to stimulate the sale by bringing him up, though. Tell me what you are willing to take to do the sale right now, and I can have the money wired into your bank account today.

We both know the last deal we discussed is grossly overpriced, and that’s the reason I decided to walk away from it.

Give me a realistic number, and let’s see if I can get this money to you today.

I brought up the trademark to Larry because even though I own the mark on thesis.com, it could be used for another business so long as it wasn’t a website software business. Automattic couldn’t use the mark unless they suddenly started selling tractors.

There was more back and forth, and Larry revealed that Matt had allegedly offered $100,000 for the domain. I still thought this was phony and just intended to get me to agree to a deal, but at least I now knew thesis.com could be had for far less than $150,000.

Unfortunately, further negotiations went nowhere, because although Larry had been willing to offer Matt a $100,000 deal, he was only willing to go down to $115,000 for me. That said, I didn’t think the domain was worth $100,000, much less $115,000!

I still assumed Matt was just a clever pawn to negotiate a higher price, and I made my final offer of $37,500.

Again, I didn’t see how Matt could justify buying the domain for $100,000. Because of my trademark, there was no way he could legally use the domain for Automattic, and therefore, I didn’t believe there was a reason for him to spend that much money.

Of course, Larry declined my offer, and I never heard from him again.

The State of the Word at WordCamp San Francisco 2014

By early November 2014, I hadn’t thought about thesis.com for months. One day, however, a friend sent a message asking if I had seen Matt’s remarks during the State of the Word Q&A session at WordCamp San Francisco…

Beginning at 4:40 in this video, an audience member asks Matt a question about the relationship between WordPress and premium Theme providers.

Matt responds with a smirk and says:

“We have had some problems with Themes that violated the WordPress license…you can go to thesis.com to learn more about that. Type it in. Seriously.”

If you type the domain into your browser, you’ll see that thesis.com redirects to Automattic’s property, themeshaper.com.

Larry hadn’t been bluffing after all.

Automattic now owned thesis.com, and they were redirecting it to their own property.

And right after Matt appears to gloat about owning thesis.com, he says:

“…but I feel like that is something where we stay true to our principles.”

Principles? Matt spent $100,000 to buy thesis.com—a domain in which he had no legitimate business interest—forwarded the domain to his property, and violated my trademark.

This is ironic considering how vigilant Matt has been about protecting the WordPress trademark—especially as it relates to domain names.

This felt like a “do as I say, not as I do” situation, and it also seemed to be reviving the licensing disagreement Matt and I had—that he won decisively—back in 2010.

Unfortunately, because of the way trademarks work, I was legally obligated to protect my trademark even though I would have preferred to leave this alone.

A Duty to Protect My Trademark, Just Like WordPress

Before I registered my first trademark, I believed trademarks accomplished two things:

- They establish a business asset related to one’s brand; and

- They make your business and brand look more official and important.

While I still think the above items are true, I can now add a third item based on my experience:

Trademarks shackle you with a formal responsibility to protect your brand in the face of challenges.

As far as trademark law is concerned, this responsibility is described as a “duty to protect one’s mark(s).” Failure to act on this duty could mean a forfeiture of the trademark(s) if challenged in court.

(For most businesses, this means spending a significant sum of money on lawyerly stuff every time your trademark is violated or infringed upon in some way.)

This is a big reason why WordPress has been so vigilant about pursuing—and shutting down—domains that include “wordpress” in the name. They have a duty to protect their mark.

Of course, this is also precisely why I had to take action once I learned thesis.com was being forwarded to themeshaper.com.

Despite Automattic’s ownership of the domain, if it were not being used in any way (i.e., not resolving to anything), then no action would have been necessary, and I would have done nothing.

However, because it was being redirected to themeshaper.com—which operates in the same market space as Thesis—I was forced to protect my mark.

There are many ways to protect trademarks, but these were the most appropriate options given my situation:

- Send a cease and desist to Automattic asking them to stop forwarding the domain (cheapest option, but it relies upon the other party being compliant in order to work). If I did this, I was worried Automattic would just sue me so they could pick their court.

- Open a Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) hearing and attempt to have an ICANN forum rule on one or both of the following:

- Require that Automattic stop forwarding the domain

- Determine that Automattic acquired and was using the domain in bad faith, and based on that, grant the domain to the trademark holder (me)

- File a federal trademark infringement suit against Automattic. Frankly, I did not want to push this far. I was hopeful that if the board of Automattic saw what had happened, they would at least agree to stop infringing on my mark.

But based on Matt’s comments from WordCamp San Francisco 2014 (video linked above), I felt Automattic had purchased the domain in a specific attempt not only to prevent me from getting it, but also to, for lack of a better term, show me who is boss.

In legal terms, this amounts to an argument of “bad faith.” In UDRP cases, bad faith is a deciding factor in whether or not the current domain owner is required to stop infringing activity or give up the domain altogether.

Given available evidence—and especially the forwarding of thesis.com to themeshaper.com—my counsel and I agreed that we had a very strong case for the bad faith argument.

If this argument were upheld in the UDRP, then I would likely end up owning thesis.com. Although this was unexpected, it certainly seemed like a positive potential outcome for the future of Thesis.

In addition, considering Matt has been so vigilant about protecting the WordPress trademark in domain names, I believed there was a clear precedent set by Matt and the WordPress Foundation in my favor.

From the perspective of ideological consistency, if you require that everyone else adhere to your requests for trademark protection, then you ought to extend the same courtesy and respect to others.

Based on their actions with thesis.com, I realized Automattic did not think these same rules applied to them.

Thus, I decided to open a UDRP case with the goal of being granted thesis.com due to bad faith on the part of Automattic.

A Curious UDRP Case Ruling

I’ll spare you the boring details of UDRP proceedings, but here’s what you need to know to understand this situation:

In a UDRP case, the Complainant (me, in this instance) initiates the dispute, the Respondent (Automattic) responds to the claims made by the Complainant, final terms are established, and then the hearing takes place.

In order for me to win the dispute, the UDRP court needed to rule in my favor on all of the following requirements:

- the domain name registered by Respondent is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which Complainant has rights; and

- Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name; and

- the domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith

After some back and forth, it was clear both parties agreed that points 1 and 2 above were likely satisfied. The question was whether or not the bad faith argument would hold.

In its official response to the UDRP, Automattic admitted they were, in fact, forwarding thesis.com to themeshaper.com.

Thanks to both this and Matt’s comments at WordCamp, it seemed likely the UDRP would rule in my favor on point 3, and thus, I would be awarded the domain.

To avoid a potential loss and also provide me with some “incentive” to settle, Automattic’s attorneys took a different tact and opened a request with the USPTO in an attempt to cancel my trademarks.

Obviously, if the trademarks were to be cancelled, I would no longer have a claim on the thesis.com domain.

With cards on the table, both sides had a chance to negotiate a settlement before July 9—the date on which the UDRP ruling was scheduled to drop.

Automattic’s attorneys drafted the original settlement, which included the following terms:

- Automattic would keep thesis.com

- Automattic would withdraw the federal trademark cancellation request

- I would withdraw the UDRP

- Both parties would mutually release one another (agree not to sue over this issue in the future)

Nothing in the original settlement addressed the trademark infringement, and since this was the reason I took action in the first place, I added a requirement that Automattic no longer infringe upon my mark (which would mean they stop forwarding the domain).

At this point in the proceedings, I agreed to the settlement. Automattic had ratcheted up the pressure in a heavy-handed manner, and being a small business owner (and a new father), I thought it made no sense to involve myself in this any further.

Although I was going to lose, I was also going to defend my trademark (even if somewhat unsuccessfully) and retain it in good standing.

On the morning of July 8, Automattic sent over the finalized settlement, and both parties were set to execute it…

However, 10 minutes later—and before either party had signed the settlement—the UDRP forum issued its ruling on the case: Automattic had won because I “failed to bring sufficient proof to show that [Automattic] registered and used the disputed name in bad faith.”

The forum went into specifics about the insufficient nature of my claims:

The Panel notes that Complainant did not include an exhibit showing that thesis.com redirects to a webpage owned by Respondent. The Panel suggests that the submissions might point toward use by Respondent that would support findings of bad faith, pursuant to Policy §4(b)(iv) if evidence had been adduced to that effect. However, Complainant failed to bring that proof to the Panel.

My attorney did not think an addendum showing a traceroute from thesis.com to themeshaper.com was necessary since Automattic had admitted to forwarding the domain in its official response to the UDRP claim.

Personally, I was considering this part of the claim to be a done deal since Automattic had already admitted to the forwarding, and the decision actually cites that fact earlier in the opinion! (Common sense was in play here, too: Go to your browser, type in thesis.com, and see what happens.)

Needless to say, it was curious that the UDRP forum effectively threw out Automattic’s admission and awarded the case to them.

Shortly after the UDRP ruling, I sent a signed version of the settlement over to Automattic, but at the time of writing, they still have not signed.

By signing, they have the opportunity to close this chapter and put this issue behind them. The fact they have not done so suggests this may not be what they want.

Fallout from the UDRP Decision

In keeping with a warning they had given me prior to the UDRP ruling, Automattic held the trademark cancellation request open, so that issue is still ongoing.

Not surprisingly, in the 36 hours after the decision, public sentiment turned extremely negative toward both Matt and Automattic.

Many viewed the trademark cancellation request as a “burn the village” tactic designed to have a more damaging impact than the UDRP decision alone could have.

Others simply wanted to know what material interest Automattic could possibly have in a $100,000 domain name that also carried trademark implications.

Of course, the easiest way to answer uncomfortable questions like these is simply to have people stop asking them.

They could achieve this by signing the partially-executed settlement upon which they had already agreed in principle. However, they have not yet signed despite having the opportunity to do so since July 8.

And so, on July 11, in a move to outrun the onslaught of negative PR, Automattic cleverly attempted to reframe this entire issue by pivoting to a known hot button in the tech industry: Software patents.

The Software Patent Misdirection

Here’s what we know thus far:

- Matt Mullenweg and Automattic paid $100,000 for thesis.com, despite having no legitimate business interest in the domain.

- By forwarding thesis.com to themeshaper.com, Automattic willfully infringed upon my trademark.

- Matt has established a pattern of being downright militant about going after people and businesses that use the WordPress trademark in their domain names. Based on his actions here, he doesn’t think the same rules apply to him.

- I opened a UDRP case against Automattic in an attempt to get thesis.com because I believed they had acquired and were using the domain in bad faith.

- In response, Automattic opened a request with the USPTO in an attempt to have my trademarks cancelled.

- Automattic won the UDRP case on what many consider to be a controversial technicality given the fact that Automattic admitted to forwarding thesis.com to themeshaper.com.

- Despite winning the UDRP case, Automattic has refused to sign our settlement agreement and, instead, has kept the trademark cancellation request open. At the time of writing, this issue is still ongoing.

- When the WordPress community first learned about Automattic’s—and specifically Matt’s—actions in this case, many were outraged.

- WP Tavern—a WordPress news website owned by Matt’s “personal research and investment company,” Audrey Capital—is where most of this outrage was voiced. Opposition to Automattic’s conduct was nearly unanimous, but shortly after one of Automattic’s attorneys left a comment, site moderator Jeffr0 turned off comments and shut down the conversation.

- Ironically, the most recent instance of WP Tavern shutting off comments occurred when the community vocally opposed the WordPress Foundation’s aggressive lawsuit against Jeff Yablon of TheWordPressHelpers.com over trademark infringment. The pattern here is that WP Tavern shuts off comments when legal issues begin to cast a negative light on Matt.

- On Saturday, July 11, Jeffr0 posted a tweet about a patent application filed in 2012 by my company, DIYthemes. In my opinion, this was an attempt to steer the conversation away from the uncomfortable reality of Automattic’s willful and hypocritical trademark infringement. Software patents are a notoriously contentious issue within open source communities, and Matt hopes you’ll focus on this instead of his actions.

Having been involved with WordPress for over 9 years, I have seen an amazing amount of good come from this community. Most of the people I know who truly care about the WordPress project are well-meaning, astute, energetic, and happy to lend a helping hand to others. This is why WordPress has reached the massive popularity it enjoys today.

But this isn’t the first time that leadership has cast a long, negative shadow over the rest of the WordPress community. In fact, this is an ugly pattern that simply refuses to die. It even has its own hashtag, #wpdrama.

The community is WordPress. Regular, hard-working people who enjoy making things on the Internet are responsible for the WordPress you know and love.

Unfortunately, capricious leadership that is largely disconnected from the reality of the rest of the WordPress community is dragging the whole thing down.

It’s time for the community to ask itself if using $300 million in funding to purchase $100,000 domains, fund aggressive lawsuits, and fuel unending drama is properly representative of the WordPress project.

There’s nothing “open” or “well-meaning” in the examples set forth by Matt Mullenweg and Automattic.

There is a giant disconnect here, and the WordPress community deserves better because it’s full of people who are better—and more principled—than that.